CS 184 Final Project

Interactive Minkowski Penalty Optimization

Summer 2025 | Tim Xie, Andrew Goldberg, Anisha Iyer, Wesley Chang | https://xie.nz/184/final

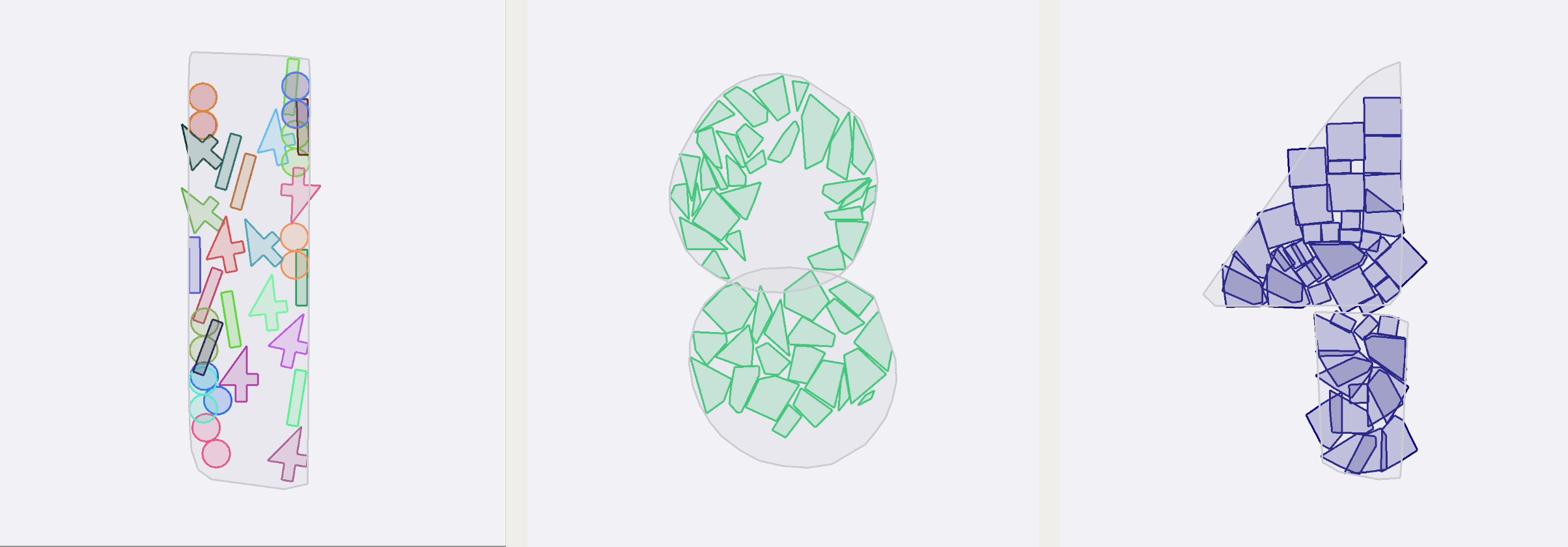

We created an interactive experience where users can draw new shapes onto a dynamic canvas where each shape’s position and rotation are being optimized based on Minkowski penalties using a gradient-based optimizer. This work was inspired by a Siggraph paper (Minarčík) which showed how the Minkowski difference between two polygons can be used in gradient-based optimization methods to enforce constraints between shapes including enforcing non-intersection and containment. The paper directly mentions that using spatial hashing as a potential improvement which we implement and benchmark alongside other optimizations. We also add interactivity, OpenGL GLSL shaders, and creative color schemes. We created our code base from scratch because the SIGGRAPH Minkowski penalty paper does not have public code.

184!

technical approach

Halfplane Method & Constraints

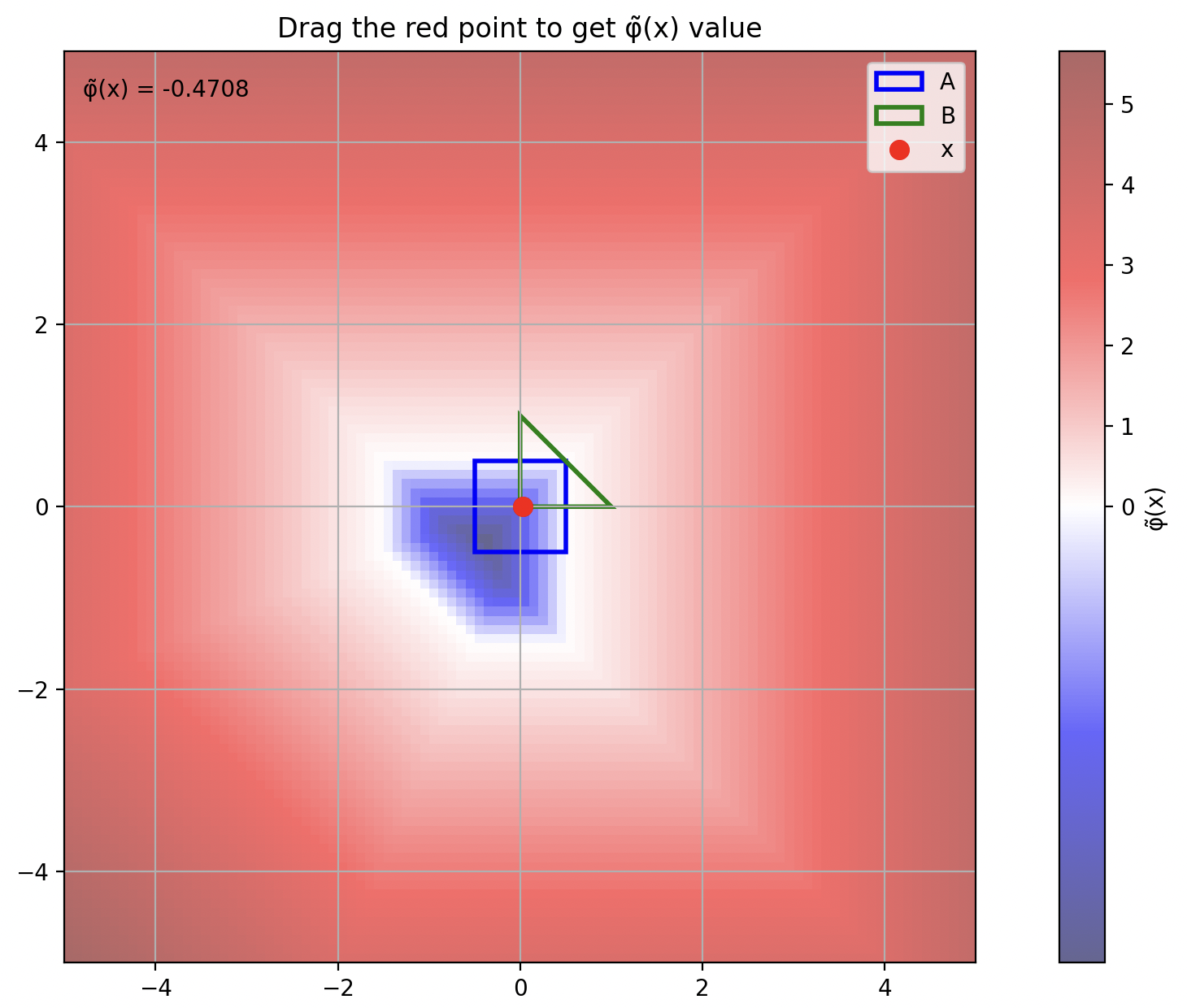

We followed an approach outlined by Jiří Minarčík which involves taking the Minkowski difference between two convex polygons and then evaluating the signed distance from that polygon at . We construct a simple, then vectorized implementation of this in PyTorch and use the objective formulations from Jiří Minarčík’s paper to implement tangential, overlapping, non-overlapping, and containment constraints.

Here is a visualization of our minkowski difference signed distance computed between a square and triangle (blue is negative distance, white is 0, red is positive distance):

Minkowski difference

Optimization & Rendering Process

We divided our code into two concurrently (multiprocess) running processes:

- An optimization process written in PyTorch which performs the optimization, publishes updated polygon positions, and updates the optimization problem as new shapes are added (through interactivity);

- A rendering process which we implement in

pygletwhich displays the polygons during optimization and colored with custom GLSL shaders and custom color schemes. It also reacts to user interaction and publishes newly drawn polygons back to the optimization process.

Improvements & Speedups

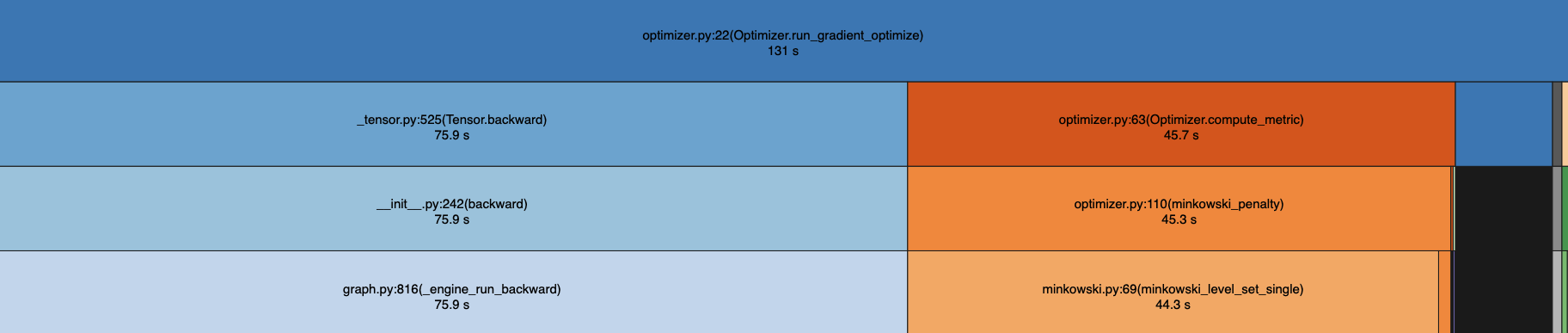

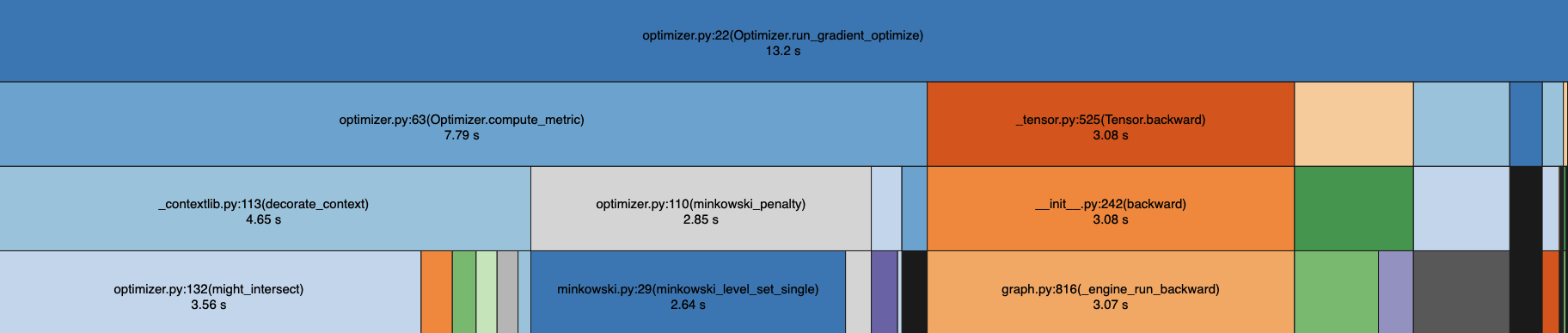

To create an interactive real-time experience, we implemented many speedups to the optimization processed, and used yappi to benchmark function and call stack times for our optimization process, combined with snakeviz to visualize the flame graphs. Benchmarks are performed on an M3 laptop unless otherwise stated and act on a scene with 70 polygons positioned randomly with a fixed random seed and parameterized with a rigid transform. Each uses an SGD optimizer with lr=.1 and converged solutions are identical because the optimizations to not impact the actual optimization steps taken.

Here is the benchmark of our implementation prior to any optimization:

No vectorization

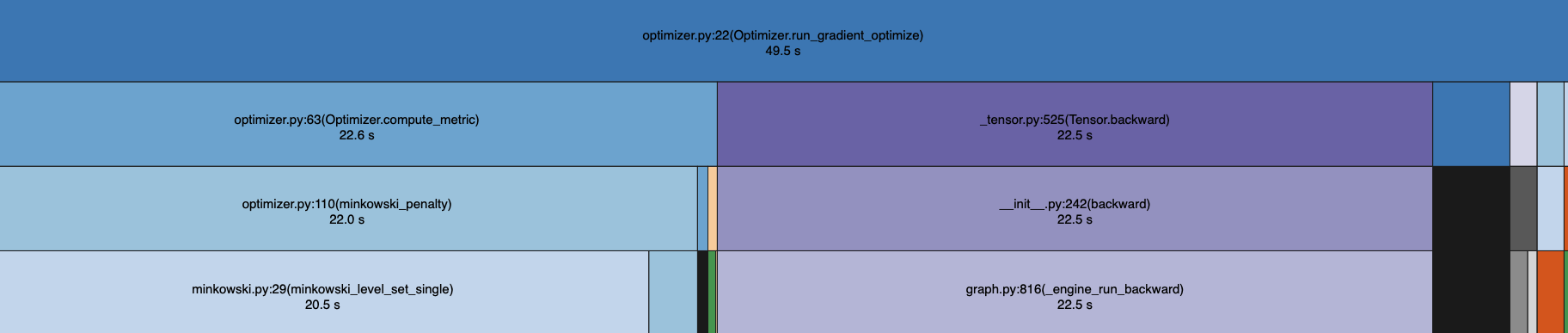

Below we detail how vectorization, a simple intersection heuristic, and spatial hashing all lead to significant speedups.

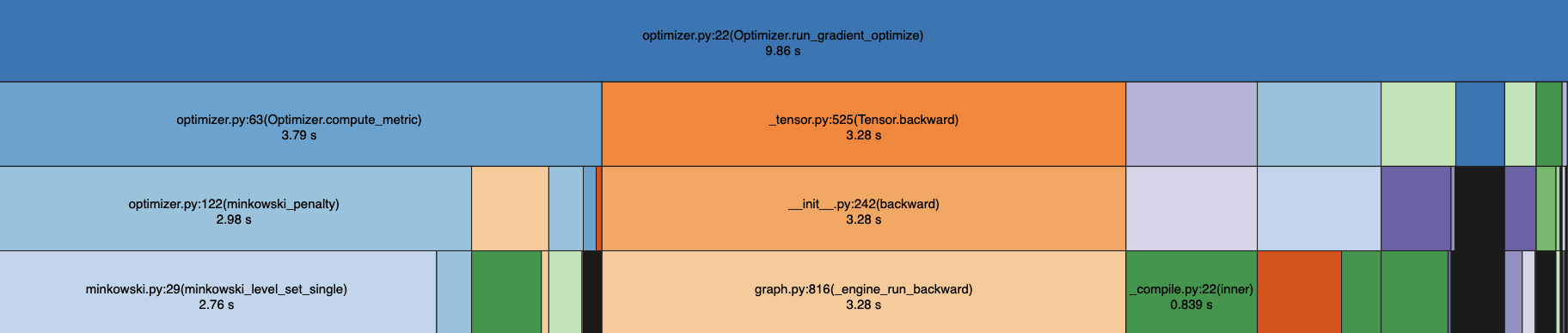

Vectorization

We vectorized the computation of the signed distance of a vertex to all edges of the polygon and the computation of the outward pointing unit normals for each edge on the polygon. This led to a significant improvement compared to our initial for-loop implementation

Vectorization only

A very simple, but significant speedup is to use a simple heuristic to check if two polygons might intersect. If they have non-overlapping constraints and we can guarantee they don’t intersect we can avoid an expensive metric computation. To start, we took the mean of the vertices of each polygon as the center of a circle and the distance to the furthest vertex from the mean as the radius. Then, we can do a simple circle intersection test and if they don’t intersect we avoid computing the minkowski penalty since we know the gradient will be 0.

Circle intersection heuristic

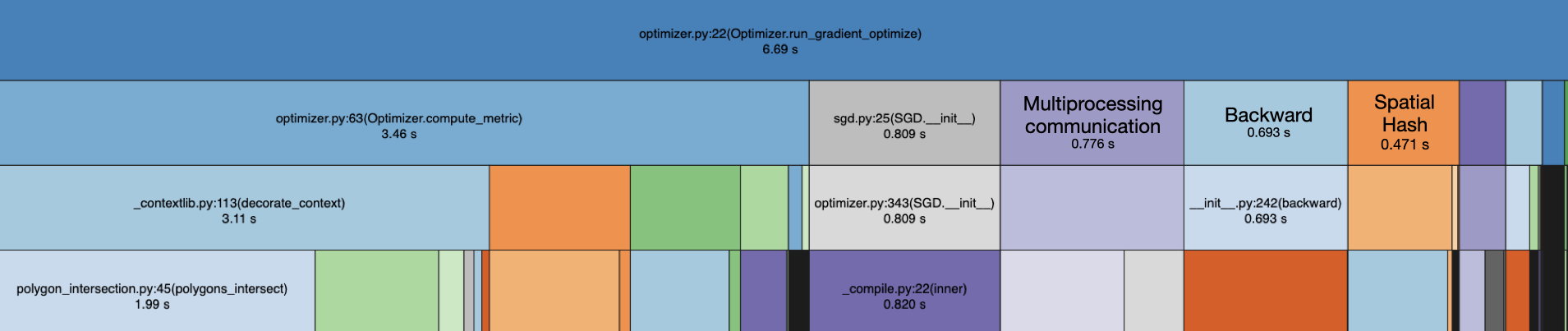

Spatial Hashing

Similar to the Uniform Spatial Partition ray-tracing acceleration structure described in class, we implemented our own spatial hashing based on a uniform grid. After each optimization step we construct a spatial hash grid for each polygon in its new position.

We start by taking the axis-aligned bounding box for each polygon, and for each cell that overlaps the bounding box, we add the cell coordinates as the key and polygon’s index as the value. We add a reverse mapping between the polygon’s index and the cell it overlaps.

With the spatial hash structure we query a polygon and get all polygons whose bounding box shares a grid cell with the polygons bounding box. We do this by using the index to cell map to get the list of cells the query polygon is in. Then we iterate over each cell and update a set to include all polygons in each cell bin. This provides nearby polygons which we then compute the Minkowski penalty on.

With the simple intersection heuristic the algorithm was still (where is the number of polygons), as for each polygon we needed to check all other polygons. With spatial hashing the algorithm is linear with respect to the number of polygons, but has differences depending on polygon density and has complexity related to polygon areas compared to cell size. There’s some overhead in reconstructing the spatial hash structure, but from analyzing our flame graph we see that it is not a large bottleneck.

Spatial hashing

Finally, we utilize the Separating Axis Theorem to check if two convex shapes intersect before running the Minkowski difference. This works by projecting both polygons onto axis which are normal to either polygon’s edge. This computation is somewhat similar to the Minkowski difference signed distance computation because it requires taking all the normals and computations related to each edge, but it doesn’t need to keep track of gradients. Also it will exit early if polygons don’t overlap which is often since polygons are often nearby with overlapping bounding boxes, but not intersecting.

Full optimizations

Note that this polygon intersection test alone is slower than using only spatial hashing ( seconds vs seconds), but combining the two is very effective.

We also attempted to run the code using cuda in PyTorch, but found this led to a slightly slower result likely due to the sequential nature of our implementation which can’t take full advantage of GPU parallelism. It’s difficult to vectorize further due to having different sized polygons and branching.

Convex Hulls

We take the convex hulls of the non-convex shapes and the interactive drawing (optionally) to speedup the initial computation through a “coarse-to-fine method” - this allows us to quickly find polygon positions using the convex shape (which is ), allows for much better interactivity.

Interaction We use Pyglet’s event-based mouse API to place waypoints at a fixed screen space distance as the user clicks and drags their mouse on the canvas. These new polygons are then communicated back to the optimizer process using the mp namespace and added to the rendering and optimization with new parameters registered to the optimizer.

Decomposition & Non-convexity

We decompose non-convex shapes using a triangulation method with shapely, to break down into convex subpolygons, which are easily optimized. The loss is calculated by taking the union over all subpolygons, contributing to the final shape. The non-convex shapes are pre-processed, and interactive new shapes are calculated upon drawing. Non-convex shapes are hard to work with, and we were only able to implement the decomposition and Minkowski difference for NO_OVERLAP shapes - but hope to implement it for CONTAINS in the future.

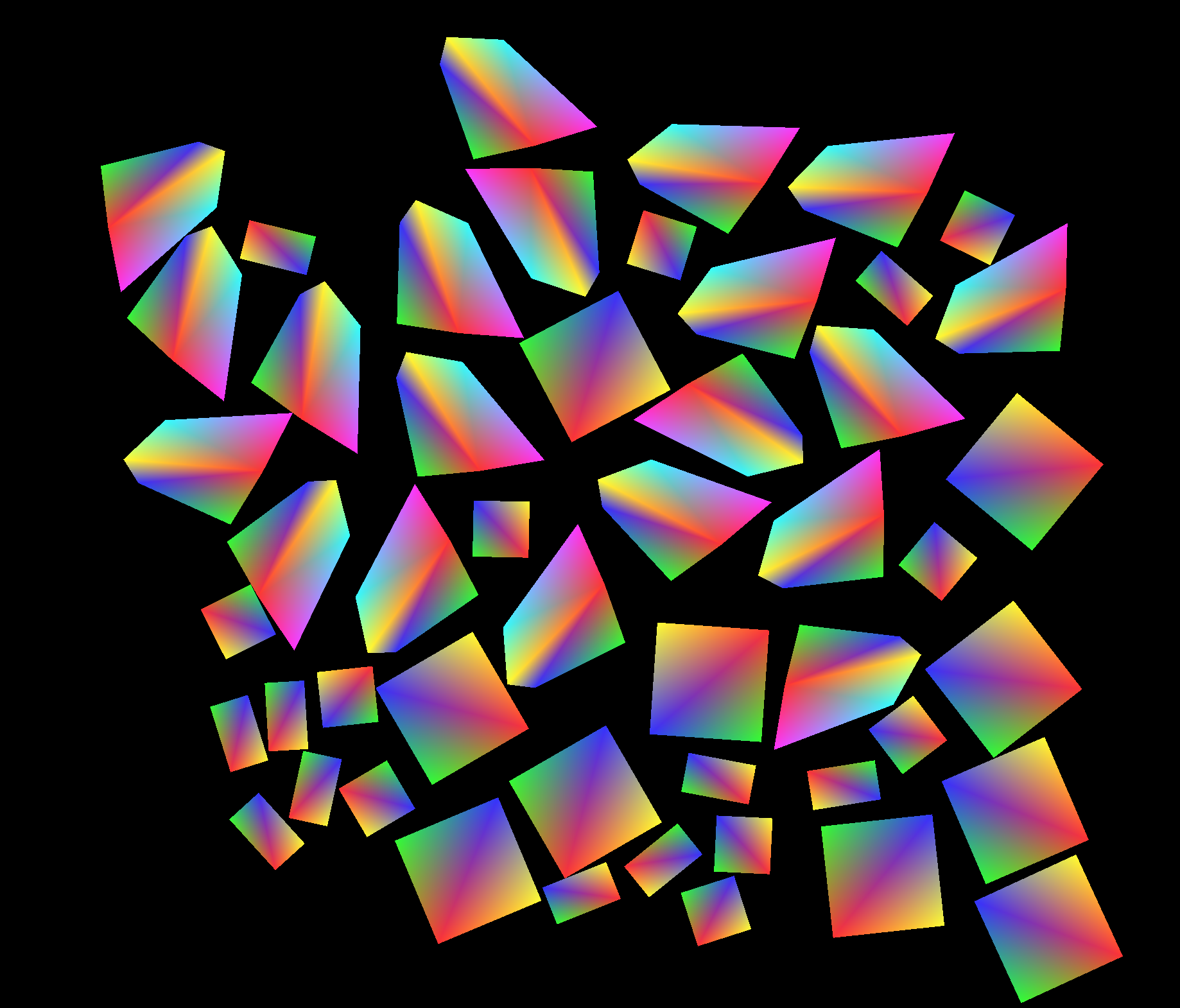

Color & Shaders To render polygons using GLSL shaders in OpenGL we triangulated by connecting one vertices to sequential pairs and gave a color to each vertex. One of the shaders we played with took in rainbow colors for the vertices and interpolated the values for the fragment shader giving a cool rainbow effect. To get this to be smooth we had to ensure that each vertex was being assigned the same color across all the triangles it was part of. Note that this only works for convex polygons and for other renderings we use higher-level APIs.

GLSL Shader!

We mainly present renders with a modular PyGlet system, supporting static palettes (rainbow, pastel, gradients), interaction-type coloring, and dynamic color schemes that change in real time based on optimization state. A built-in legend explains the meaning of each color, and users can toggle through schemes interactively to view different optimization metrics. These visualizations map optimizer metrics, such as overlap penalties, movement velocity, and energy levels, directly to color, giving us intuitive insight into constraint enforcement and helping diagnose convergence behavior as it happens.

results

Please see the video here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TBlc0vCUmiSlsD0MG2ydm6ta8E5SAqlz and the slides here: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1d37xybU5cOCSDob-8u5DoBmP57MP4Su3-Cuy1o5udPo !

references

- Minkowski penalties:

- website: Minkowski penalties

- supplement paper: supplement

- Penrose constraint solver with Minkowski penalties: https://github.com/penrose/penrose/pull/648

- other PRs related to this:

- computing intersection depth of polyhedra: paper

- accelerated spatial hashing:

- locally perfect hashing: https://haug.codes/blog/locally-perfect-hashing/

- hashing paper: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~kaess/pub/Dong23pami.pdf

- grid hashing: nvidia grid hashing paper

contributions

- Andrew: Initial ideation, differentiable minkowski difference, parameterization and infra code, optimizer testing, benchmarking, vectorization, circle heuristic, spatial hashing, GPU attempt, matplotlib and pyglet plots and live renders;

- Tim: Non-convex decomposition, coarse-to-fine speedups, convex hull optimization, visualization & interactivity, initial colouring, GLSL shaders & further colouring. (Website maintenance/updating/publishing writeup);

- Wesley: Color based energy functions and sorting (w/ Anisha), initial working demo;

- Anisha: Color based violation and energy functions (w/ Wesley), diffVG tests, hyperparameter tuning, dynamic color schemes in matplotlib, pyglet, and GLSL to visualize constraint enforcement.

ai acknowledgement

- Andrew: I used AI for many of the parts I worked on. To understand parts of the math I copied parts of reference material into ChatGPT and worked to understand it, although I translated it to PyTorch myself. For debugging I often used ChatGPT for extensive help with Pyglet (including generating code examples) and settings on matplotlib plots. For example I learned about MatplotLib TwoSlopeNorm from ChatGPT for minkowski difference plotting which I would’ve never thought to look for on my own! I also used ChatGPT to come up with the right Python multi-procesing tool (using mp namespaces which I didn’t know about previously and makes a lot more sense than a stack or queue for our use case) and to discover Yappi and SnakeViz for benchmarking which I also hadn’t used previously. I also used ChatGPT in creating a polygon intersection test heuristic (mainly for vectorization). I also used AI for the pixel_to_ndc function used in rasterizing triangles in OpenGL because in debugging my code I had expected to need to pass screen space coordinates for OpenGL and I used ChatGPT for help in resolving the bug.

- Tim: I wrote most code myself, with help of ChatGPT to generate tasks, boilerplate and some visualization functions. Asked ChatGPT to help debug parts that I was stuck with, and general conceptual questions. Definitely more ChatGPT used on this project than the homeworks.

- Anisha: I used AI to provide semantic advice for the color scheme README and improve readability of contextual print statements for color schemes, which discuss the legend for color changes of polygons during constraint enforcement for each dynamic color scheme. I also asked AI to suggest test cases for intended user-functionality of dynamic color schemes, which I then implemented in Python.